I relish the abundance of relatively—and poignantly—dud paintings in “At the Dawn of a New Age: Early Twentieth-Century American Modernism,” at the Whitney Museum. With an emphasis on abstraction, the show features a number of rarely exhibited works, most owned by the museum, that were made during the learning-curve years—at full tilt by 1912—of artists on these shores who strove to absorb the revolutionary innovations that had originated in Europe. Occupying the museum’s eighth floor, the array provides a sidelight (or prequel) to the Whitney’s selection of touchstone pieces from its collection, dating from 1900 to 1965, on the seventh floor. That long-running installation parades feats by American adepts—Edward Hopper, Alexander Calder, Jacob Lawrence, Willem de Kooning—along various routes, with propitious detours toward world-beating Abstract Expressionism, Pop art, and Minimalism.

“At the Dawn,” organized by the curator Barbara Haskell, samples provincial talents who had plenty of moxie but remained shallowly rooted in the dashing radicality with which Europeans eclipsed embedded traditions. The aspiring Americans thrilled to the explosion but tended to be hazy on exactly what, in prior art history, was being blown up. Their frequent ingenuousness tantalizes. It is a fact of the art-loving experience that serious but failed ambitions teach more about the tenor of their times than contemporaneous successes, which freeze us in particular, awed fascination.

When something doesn’t quite cohere, you can see what it’s made of. Sources and intentions glare from the canvases. Historical museums should incorporate more of such stuff, to contextualize the happy shocks of excellence, which, on the two floors of the Whitney, include hits in almost their initial at-bats by John Marin, Arthur Dove, Stuart Davis, Georgia O’Keeffe, Florine Stettheimer, and the ever-amazing Marsden Hartley, whose powers of emblematic abstraction peaked in 1914 in Berlin, during a sojourn from his native Maine, and persisted sub rosa throughout his later Southwestern and New England landscapes and homoerotic figurations. Those artists promulgated authentic declarations of independence.

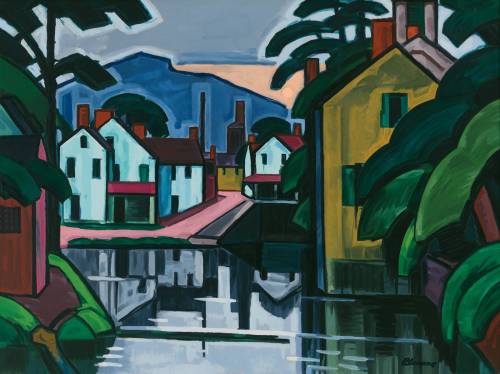

“Old Canal Port,” by Oscar Bluemner, from 1914.Art work courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art

The distinguishing test, for me, is scale, irrespective of size: all a work’s elements and qualities (even including negative space) must be snugged into its framing edges to consolidate a specific, integral object—present to us, making us present to itself—rather than a more or less diverting handmade picture. Among the painters in “At the Dawn,” that sort of resolution eluded the likes of the Chicagoan Manierre Dawson, America’s first true abstractionist and a highly promising artist until, in 1914, he withdrew to run a farm in Michigan; the color stylists Stanton Macdonald-Wright and Patrick Henry Bruce, whose lastingly seductive but fitful beauties went pretty much nowhere; and the Russian-born Max Weber, whose extraordinary “Chinese Restaurant” (1915) mashes up, at a go, assorted tactics of Cubism and never fails to beguile me even as it doesn’t really work at all.

Sculptures by Elie Nadelman, who was born in Poland, and Gaston Lachaise, who emigrated from France, memorialize a New York-based, sensuously decorative modernist chic. Many other artists in the show were immigrants, too: German, Italian, Polish, Ukrainian, Lithuanian, Japanese, Chinese, and British (does Canadian count?), flavoring a cosmopolitan melting pot. Works by several of the newcomers are close calls in terms of quality. Visual rhapsodies by the Italian-born Joseph Stella include a game attempt to represent music with the frenetic “Der Rosenkavalier” (1913-14). Plangent landscapes by the German-born Oscar Bluemner, influenced by the Blue Rider movement (which had convened German and Russian avant-gardists in Munich), suffer from a certain cautiousness. A Ukrainian unfamiliar to me, Ben Benn, went native with a creditably sombre abstraction, “Cowboy and Horse” (1917). In general, though, engagements with American subject matter are rare in the show. Imported internationalism reigns.

Of passing reward are stabs at mysticism by lately rediscovered mavericks, including the German-born Californian Agnes Pelton, the subject of a delightful but not entirely convincing retrospective at the Whitney in 2020. Pelton’s richly hued, luminous “Ahmi in Egypt” (1931), which depicts a swan beneath cascading abstract symbols against a black ground, anticipates a penchant among some present-day painters for themes of the otherworldly. (This penchant was given a boost in 2018 by a sensational show, at the Guggenheim, of immense proto-abstractions by the early-twentieth-century Swedish spiritualist Hilma af Klint, who had long been all but forgotten.) “Ahmi in Egypt” is lovely but verges, to my eye, on suggesting an overqualified greeting card. Of related relevance is a watercolor with pencil drawing by the chronically underrated Charles Burchfield, “Sunlight in Forest” (1916)—dark trees pierced vertically by a tonguelike shaft of white sunlight—which heralds the soulful idiosyncrasy of Burchfield, a Lutheran mystagogue of small-town and rural epiphanies who was close friends with Hopper. His enraptured art keeps looking stronger, in hindsight.

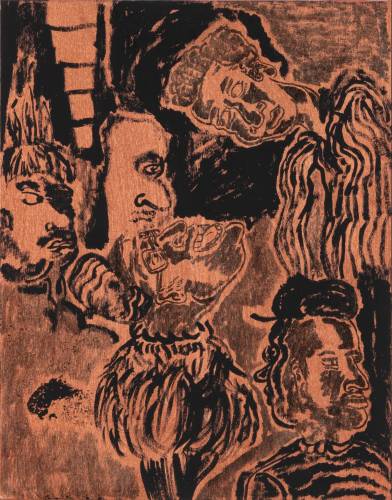

In addition, room is made for excitingly Expressionist woodcuts from the mid-twenties by the Black artist Aaron Douglas, which include a jagged response to Paul Robeson’s performance in the Eugene O’Neill play “The Emperor Jones,” and for a piquantly symbolist tarot deck that was designed by the American-educated British illustrator Pamela Colman Smith in 1909 but that remained unpublished until more than a decade later. Such items plunge us into a bygone cultural ferment whose paladins may have sputtered in their aims but who pitched into them enthusiastically. Though they were only sometimes personally allied, they evoke, en masse, a national team effort.

The show occasions time-travelling connoisseurship, to sort out instances of brilliance from more prevalent disappointments. You are there, immersed in peaks and valleys of an effervescent day and age. I don’t expect your judgments to match mine. I recommend attending with an argumentative companion. The very unevenness of the offerings makes for fine sport. When you think about it, art appreciation parallels all manner of games that people play—not least baseball, the individualistic American invention that has just lost its Homeric bard, Roger Angell, to unexpectedly devastating effect for some of us—with the pesky difference that art does so without a scoreboard and, eschewing inning breaks, never ends.

“My Name Is,” by Walter Price, from 2022.Art work courtesy the artist / Greene Naftali

Several younger painters today play at hybridizing representation and abstraction. It’s a mode of have-it-all eclecticism that is frequently redolent of the wishful artists’ statements that art schools require their students to write—a godforsaken prose genre that is, at best, wholesomely cynical. (Graduates in literature aren’t obliged to supplement their theses with paintings.) But here I am, wowed by “Pearl Lines,” a large show at Greene Naftali of paintings and drawings by Walter Price, thirty-three years old, who deploys just such crossover stratagems with sterling discipline and untrammelled liberty. The forms of his eloquently colorful art, which mingles imagery of banal manufactured objects with evocations of fire and water, can seem at once to fly apart and somehow to precipitate ineffable harmonies. They qualify as decorative in the way that climbing a Himalayan peak might be deemed recreational.

Price was born in Macon, Georgia, and decided to become an artist while in the second grade. Straight out of high school, he served four years in the U.S. Navy, chiefly to take advantage of the subsequent G.I. Bill financing of his art studies at Middle Georgia College (now part of Middle Georgia State University) and the (recently defunct) Art Institute of Washington, in Arlington, Virginia. He’s a Brooklynite today. These and other data points pepper an interview, in the Financial Times, that was conducted last year by the Nigerian American critic Enuma Okoro. A “dance with whiteness” is how Price describes his thinking behind work that he made during a residency in London. He regards himself as “political, but not overtly,” aiming to “make people comfortable with being uncomfortable,” both aesthetically and by way of any worldly association that occurs to them.

Price said that he shuns all social media: “Too much looking and not enough thinking.” The abnegation pays off. Inexhaustibly surprising smears, blotches, fugitive lines, and incomplete patterns feel less applied than turned loose, to tell enigmatic stories of their own. The effect is redoubled in his exuberant, earthy drawings in which, often, faces and figures share spaces with visual equivalents of improvisatory jazz. I can think of no precedent for Price’s style-defying style except in the spirit, though not the look, of certain decomposed compositions by Cy Twombly. There are occasional longueurs, as seen in dotted lines that seem overly calculated to knit a surface. But even these glitches evince Price’s compulsion to risk all manner of painterly tropes. To think is to do, for him. Staggeringly prolific, he recalls Oscar Wilde’s doctrine of mastering temptations by succumbing to them.

You must physically encounter Price’s paintings to grasp their dynamics. Scale is germane: both internally, in the jostle of mismatched marks and textures, and externally, relating to the proportions of your body. This may be true in general of any effective painting, but it is essential in this case. It enables an exhilarating sense of participation, as if, by viewing a work stroke by stroke, you create it yourself. The artist has left you alone with it as he departs toward something not quite altogether but manifestly else, starting from scratch again and yet again. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com